|

|

|

|

This is a old article. Parts have been superseded by new research. Some, but not

all of that research has been edited into the article. The major change is that the Exodus did not

begin until the morning of the 15th of Aviv after sunrise., and they completed it only in the night between the

15th and 16th, the night of the vigil. This is fully explained in the Chronology Book. This paper is

being retained because it is still of some scholarly value to me and others. Daniel Gregg.

§503 These views are very much related to the Sabbath Resurrection, and need to be addressed in relation to it, especially if the Messianic Community is to practice the Torah correctly. For an incorrect view of the resurrection and the renewed covenant can lead to observing the Passover in an incorrect way. For example, Coulter teaches that the Biblical 'Old Covenant' passover was changed into the 'New Covenant' Passover, in which he says:

"Jesus clearly nullified the observance of the Old Testament

Passover with the introduction of the new symbols. The footwashing and the

new symbols of unleavened bread and wine have replaced the former paschal

meal of lamb and bitter herbs" (pg. 212, The Christian Passover).

This, of course, is nothing less than an overturning of Torah.

§504 This makes Coulter's teachings no better than the rest of Christendom, which uses the same argument. It also happens to contradict Yeshua's own words in Matthew 5:17-20 and 23:1-3, as well as the words of Coulter himself, 'The law and the prophets are still in effect.' (pg. 209).

§504.1

Another Promoter of the Neo-samaritan Passover was the late Harry Veerman,

better known by his adopted name Phinehas Ben Zadok. I met Mr. Veerman

in Redlands California in 1994 and we discussed the first edition of my

book at a Sabbath service in Dr. Paul Goodley's home (Congregation Adat

Elohim Chaim). We exchanged books. The name of his book was

Which Day is the Passover? Sadly, Mr. Veerman rejected the

substance of The Sabbath Resurrection out of hand. Shortly after

ordering a subscription of The Journal of Messianic Scholarship (5/25/95)

he passed away. He and his wife also published The Good Olive Tree

newsletter. To this day Phinehas' writings are having a great

impact on the Messianic community in regard to the observance of Passover

and Pentecost, which is why I am documenting this here. More

recently Avi Ben-Mordechai has written a booklet advocating the neo-samaritan

Passover (Messiah: Understanding His Life and Teachings in Hebraic Context,

Volume 2; A Millennium 7000 Communications Int'l Publication, First edition,

9/1997, 1000 copies).

.

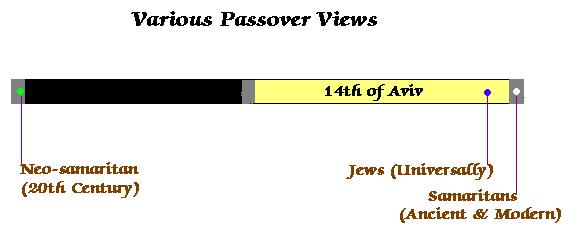

§505 As mentioned in §501 the Jewish Passover was slain on the afternoon of the 14th of Aviv and eaten on the 15th. This view is in accord with that of the Pharisees and the Rabbis. Now, the Protestant Reformation did not error too greatly in the principle of sola scripture (scripture only), when it applied to unbiblical traditions or when applied to traditions about which the scripture had nothing to say, but in those cases where scripture is ambiguous, long traditional practice is valuable, especially when the traditional practice is not negated by any scripture or any long standing contrary tradition. All extra biblical 'history' is a species of tradition. For this reason, what is recorded in Jewish traditions must be sorted out. It cannot be rejected out of hand.

§506 For example, the determination of the new moon by the first visible crescent in Jerusalem is the oldest and most correct tradition for fixing the time of the new moon. The scripture does not tell us precisely how to fix the new moon. But the Pharisee's traditional practice of fixing the new moon in the Second Temple Period fits best, and most simply, with the scripture data.

§507 Another example is that scripture does not tell us how to exactly conduct a religious service, yet tradition is a valuable teacher here. According to customary practice a religious service ought to have singing, prayer, scripture reading, a lesson or sermon, time for questions and answers and a general fellowship time. That is the traditional interpretation of the command to have a holy "convocation" or "meeting" on the Sabbath day (Lev. 23:1-3).

§508 So when a matter is ambiguous or open to interpretation, the question is, "Which traditional sources are most reliable?" The answer may be surprising to some, but it might seem obvious to modern day Rabbinic Scholars. Yeshua had a definite answer to the question; he said: The scribes and the Pharisees sit in the seat of Moses. All that they say, do and observe' (Mt. 23:2-3a).

§509 Yeshua could easily have said this about the Sadducees, or the Essenes, or some other obscure sect of Judaism, but he did not. When it came to legal opinions, he endorsed the Pharisees. He did not endorse the Samaritans, but said, "Salvation is from the Jews," (John 4:22)

§510

Therefore, we should pay attention to Jewish explanations of the Hebrew

language, and their interpretation of ambiguous phrases. For to them

are entrusted the oracles of God. The issue of the correct time of

Passover, however, can be more or less completely resolved from the scriptures

alone, if we follow a careful practice of logic and start with known facts

first. The timing of the Sabbath day will prove foundational in this

respect.

.

§511

There, are many definitions of the word "day," which can be confusing if

we do not start with a known quantity. The Sabbath lasts from sunset

to sunset. This was briefly covered in §17.

Long standing Jewish tradition is unanimous regarding the beginning and

the ending of the Sabbath. Furthermore, there are no contrary traditions

that have made any significant impact on Jewish observance. The sunset

to sunset reckoning of the Sabbath is supported in several places in the

scripture.

The foremost place, of all places, that the timing of the Sabbath is taught

is in Exodus 20:8-11 -- the sabbath commandment itself. How can I

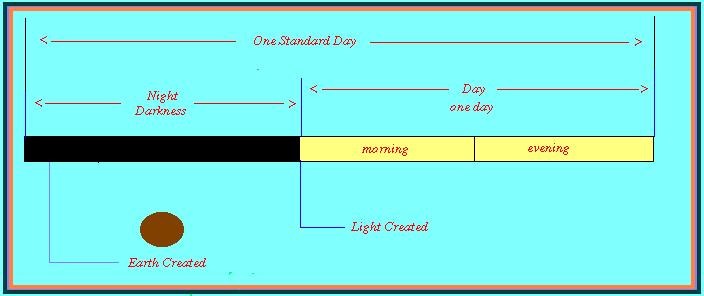

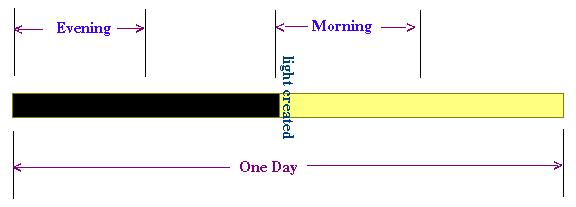

say this? Exodus 20:11 says that Yahweh created the heavens and the

earth in "six days". Therefore, the "formless" "earth" in Gen. 1:2

was created within the six days of creation. Now light was created

on the first day (Gen. 1:3-5), yet the empty earth was made before light

(Gen. 1:2), because we are told that "darkness was over the surface of

the waters" (Gen. 1:2) prior to the creation of light. Since, light

was made on day one, and the earth was made before light, the only way

the earth can still be made within the confines of six days is to be made

on day one also. Yet is was dark. What does Yahweh call the

darkness that was over the surface of the deep? He calls it "night"

(Gen. 1:3-5). And the light he calls "day." There you have

it. The sequence is "night" and then "day," which is to say that

Exodus 20:11 associates the night preceeding with the first day in order

to include the creation of the formless earth in the six days of creation.

See figure below:

.

Another indication of Sabbath timing is found in Nehemiah; Nehemiah ordered

that the gates of Jerusalem be shut at a certain time: "as [were] shaded

[the] gates of Jerusalem before the sabbath" (![]() )

(Neh. 13:19). Now the gates were normally shut in the near east at

the end of astronomical twilight, which is some time after sunset, hence

no command would be needed if the sabbath began when the stars came out,

but here the gates are shut as the shadows fall upon the gates, which means

it was just before sunset, and that merchants were to be prevented from

entering even though it was possible to see for another hour.

)

(Neh. 13:19). Now the gates were normally shut in the near east at

the end of astronomical twilight, which is some time after sunset, hence

no command would be needed if the sabbath began when the stars came out,

but here the gates are shut as the shadows fall upon the gates, which means

it was just before sunset, and that merchants were to be prevented from

entering even though it was possible to see for another hour.

Another text that points to sunset is Mark 1:32, "And when it became evening

at sunset (![]() )

they brought to him all who were sick." And this was the end of the

Sabbath day (Mark 1:21), because the scribes did not permit healing on

the Sabbath. Furthermore, the timing of all the rest days of Israel

can be assumed to be the same, hence the day of Atonement is "from setting

until setting (

)

they brought to him all who were sick." And this was the end of the

Sabbath day (Mark 1:21), because the scribes did not permit healing on

the Sabbath. Furthermore, the timing of all the rest days of Israel

can be assumed to be the same, hence the day of Atonement is "from setting

until setting (![]() )"

(Lev. 23:32), and since this day is a sabbath on which no work is to be

done, it follows logically that the weekly sabbath is also from "setting

unto setting." But this last definition is not as precise as the

the other two.

)"

(Lev. 23:32), and since this day is a sabbath on which no work is to be

done, it follows logically that the weekly sabbath is also from "setting

unto setting." But this last definition is not as precise as the

the other two.

Before using the definition of the sabbath as applied to Passover, we must

show that evening in the Hebrew language may mean the "afternoon," because

the lamb is to be killed "in the evening."

.

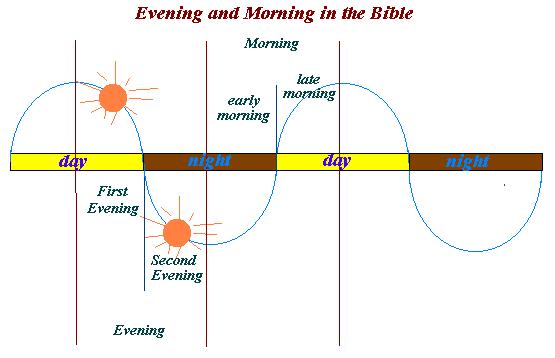

Since the Genesis 1:5 definition of "day" is "light" we must understand this as no longer than from dawn to dusk. We really do not know if there was a dawn for the first day. The light may of simply appeared. What we can say for certain is that the first day ended with the setting of the light. The first evening (erev) was the setting of the light at the end of the first day. Since there was no light to set when darkness was over the face of the earth before the first day, there was no 'erev' or 'setting' before God created light. The text, "And there was setting and there was morning: one day" (Gen. 1:5) refers to the setting at the end of the first day, and the morning at the end of the night after the first day. "One day" refers to the 'light' (dawn to dusk) that was before this night.

If we discard Gen. 1:5 and use some other definition of day, it is still clear that Exodus 20:11 regards the days as defined from sunset to sunset from its own point of view. So what if we discard the Gen. 1:5 definition of day? In that case we would have to diagram the summary statement as follows:

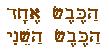

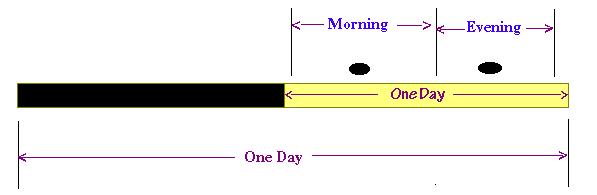

§513 Now that it has been shown that erev may mean the "afternoon," from the scriptures and traditional Jewish interpretation, and that the sabbath had a "morning and evening" sacrifice, we will now prove that our assumption that the order cannot be reversed. We will show that the specific phrase, "between the evenings" means "afternoon." (Exodus 12:6; Lev. 23:5). We will prove that it cannot be changed to "evening and morning sacrifice, so that the evening sacrifice is just after sunset on the sabbath, and the morning sacrifice later on, in the day part of the sabbath. The key text preventing a reversal of order is the passage legislating the continual offerings:

'You shall offer to Yahweh lambs, sons of a year, two to the day, a continual offering, the first lamb you shall offer in the morning, and the second lamb, you shall offer in the interval of the evenings.' (Num. 28:3-4).In the Hebrew text the lambs are numbered:

the lamb first / the lamb the second, and associated with morning and evening

so that the order cannot be reversed. Note again that both offerings

are offered in the same day: see the figure:

the lamb first / the lamb the second, and associated with morning and evening

so that the order cannot be reversed. Note again that both offerings

are offered in the same day: see the figure:

The two black

dots mark the morning and evening sacrifices. Remember, that this fits

the day as defined in Genesis 1:5 (i.e. light), and in the Sabbath commandment

(Exodus 20:11). II Chron. 2:3 requires there to be a "morning and

evening sacrifice for the Sabbath."

Now,

let us test this argument to see if any holes can be made in it.

As long as the day is from sunset to sunset, the evening sacrifice must

be in the the afternoon. The common day would allow the second offering

to be after sunset (cf. §40)

and have the two lambs on the same day, but then it would no longer be

the morning and evening sacrifice for the sabbath, because the sabbath

ends at sunset. Furthermore, it cannot be the first lamb in the morning,

and the second lamb in the evening for the sabbath if the common day was

meant, because on the sabbath it would become the second lamb on the common

day beginning the sabbath, and the first lamb on the common day ending

the sabbath. But we have seen from II Chronicles 2:3 that it is "morning

and evening offering for the sabbath." Likewise the day cannot mean

dawn to dusk in this case, because the offering in the dusk would be after

the sabbath, thus reversing the order again. For the same reason,

it cannot mean midnight to mightnight. For another reason it cannot

be noon to noon. The only allowable definitions of "day" in Numbers

28:1-4 are the two shown in the above figure.

.

§516

Therefore ![]() 'setting' in this passage means exactly what the Jews have always said

it means, the period of time between noon and sunset. The 'setting'

sacrifice was not offered after sunset, but before, during the first

setting, which is the only view that preserves the legal numbering

of the lambs on the sabbath day. It also shows conclusively that

the command to offer the Passover lamb in the evening means in the afternoon.

For the word erev is used in the Numbers passage in exactly the same way

it is used in the Passover command (

'setting' in this passage means exactly what the Jews have always said

it means, the period of time between noon and sunset. The 'setting'

sacrifice was not offered after sunset, but before, during the first

setting, which is the only view that preserves the legal numbering

of the lambs on the sabbath day. It also shows conclusively that

the command to offer the Passover lamb in the evening means in the afternoon.

For the word erev is used in the Numbers passage in exactly the same way

it is used in the Passover command (![]() ),

bayin ha-ar'bayim (Exodus 12:6), which is to say literally, "between the settings," or

"interval of the going down." The first setting begins at noon, and

the second when the sun enters (sunset), hence between the two is the period

in English known as "afternoon." "Between the evenings," is thus

sometimes loosely translated "in the evening." And it is wrongly

translated "twilight"; my research points to the possibility that

over emphasis on this definition is due to higher critical studies of the 19th

and 20th centuries originating in the liberal German School.

),

bayin ha-ar'bayim (Exodus 12:6), which is to say literally, "between the settings," or

"interval of the going down." The first setting begins at noon, and

the second when the sun enters (sunset), hence between the two is the period

in English known as "afternoon." "Between the evenings," is thus

sometimes loosely translated "in the evening." And it is wrongly

translated "twilight"; my research points to the possibility that

over emphasis on this definition is due to higher critical studies of the 19th

and 20th centuries originating in the liberal German School.

Therefore,

the Jewish Passover timing on the afternoon of the 14th of Aviv is

fully correct and justified. It also shows that Yeshua did not error

in telling the disciples to do as the Pharisees said (cf. Matthew 23:1-3).

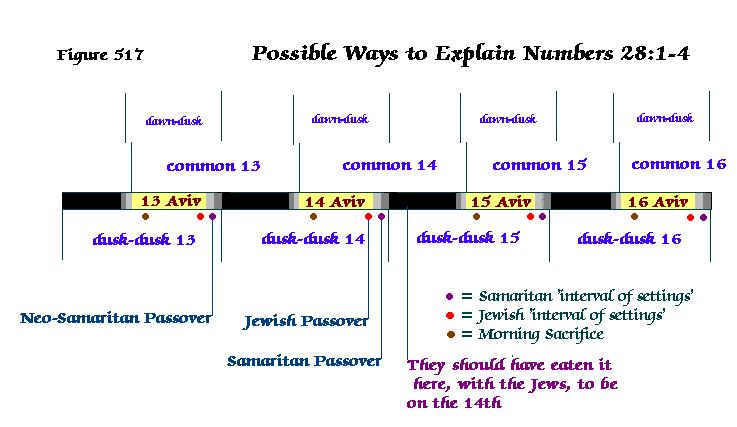

§517

Now let us explore some of the ways that the Neo-Samaritans would like

to define a day: They could possibly explain the 'day' in the passage in

Numbers 28 as dawn

to dusk, dusk to dusk, as the common day, or midnight to midnight.

We have shown already that definitions of 'day' meaning sunrise to sunset,

and sunset to sunset do not work for them. Furthermore, defining

Sabbath as sunset to sunset rules out the other definitions of day.

But what if we liberalize the definition of the Sabbath and make it from

dusk to dusk? This is an unofficial rabbinic definition (I'm sure

the Neo-Samaritans will love it), but let's try it and see what happens.

If the Sabbath is dusk to dusk, then they could have the evening sacrifice

after sunset on the Sabbath. But please note that the lambs are still

numbered, and that the second lamb still follows the first lamb on the

same day, i.e. 'two lambs to the day', 'the first in the morning,' and

the second in 'the interval of the going downs'.

Does this moving of 'bayn

ha-erevim' after sunset justify the Passover at the start of the standard

14th of Aviv rather than day part of the 14th? Not at all!

If they are going to define the day as dusk to dusk, then it is STILL the

13th day of the month, which is a violation of the Passover Ordinance.

Rather, to be in harmony with Numbers 28:1-4, they ought to kill the lamb

after sunset of the day part of the 14th, which is only hours after the

Jews would kill it, and they would have to eat it at the exact same time

as the Jews. This shows that their heresy really is heresy and not

a difference of opinion:

.

So for those

who insist that "bayin ha-erevim" can only mean after sunset, to be consistent

with the scripture, they must adopt one of these other definitions of 'day'

and eat the Seder at the same time the Jews eat it.

§518

The Passover lamb or goat was to be slain between the settings, or at the

setting of the sun (Exodus 12:6), that is between noonset and sunset on the

14th day of the month of green-ears (Aviv). As we have seen from

the two numbered lambs in Num. 28:3-4, offered the same day, the first

in the morning, and the second halfway through the setting, this time between

the settings could only refer to the afternoon. The next legal day

begins at sunset.

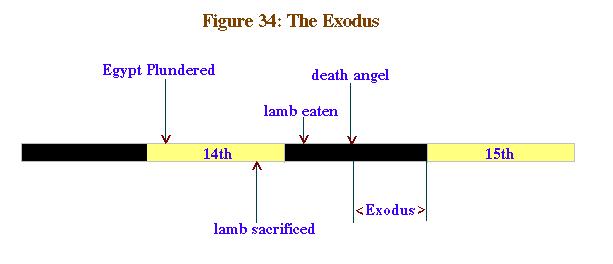

§520

The Passover lamb was to be eaten in that night (Exodus 12:8), which was

after sunset and twilight on the 15th day of Aviv. Clearly, if the

lamb was slain on the 14th day between the evenings, in the afternoon,

then "that night" would have to be the following night, viz. the beginning

of the 15th according to the standard day. However, the standard

day (cf. Fig. 6,

§39-40) may not be the best explanation for the usage "that

night." Rather, what we have is another use of the common day, in

which the night following is associated with the day.

§521

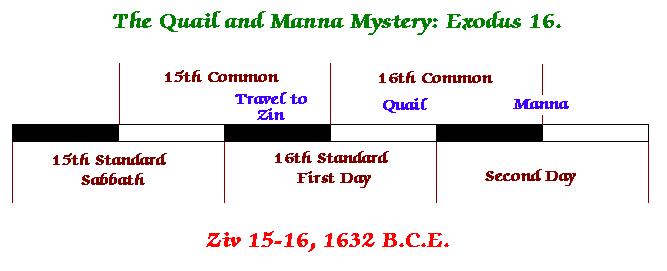

It can be shown by astronomy that in Exodus 16:1, the 15th of the second

month was a Sabbath. For the month of Ziv, the second month, began

at sunset on 4/25/1632 b.c.e. (§607), which was a Friday, the

beginning of the Sabbath, and so the 15th day was also a Sabbath day.

The previous day, the arc of vision was not sufficient (§126ff)

to place the month a day earlier (arc < 7 deg.), but for that day the

arc was quite sufficient for visibility making postponement highly unlikely

(which would only validate our argument another way).

Many have merely accepted this to be a Sabbath, because they have assumed

that manna fell for six days before the next Sabbath arrived. But

the text does not say manna fell for six days. It says, on the sixth

day, viz. Friday, that they received a double portion. If the 15th

had been a Wednesday, the manna could have fallen for only two days for

all we could have known.

§522

Fred Coulter also assumes that the 15th was a Sabbath; for the children

of Israel "had come ... to the Wilderness of Sin ... on [the] 15th of the

month" (Exodus 16:1). He then argues that God promised

to send the quail on the evening following the Sabbath, viz. after sunset,

which he equates with between the evenings you shall eat flesh (Exodus

16:12). By arguing that they could not cook on the Sabbath to eat

it, he then reasons that it must have been after sunset, so that between

the evenings means after sunset.

§523

But we must notice that if the 15th of the month is the Sabbath, then how

can the people arrive on that day without having to travel on that day!

Travel was forbidden on the Sabbath (Exodus 16:29-30). And travel

was not rest. For they had to unload the beasts, and unpack

the tents which was work! You will know if you have gone camping.

And setting up camp is also work, after a tiring march. Furthermore,

the people were hungry. They were hungry enough to complain against

Yahweh! Do you wonder why they were hungry?

The solution is found in Exodus 13:21, "And Yahweh went before them by

day in a pillar of cloud to lead them along the way, and by night in a

pillar of fire to give light to them that they might travel by night"!

Furthermore, it was full moon during that time of month, so they had a

double light. The light they received from Yahweh was the same light

that lit the earth during the first three days of creation. So they

arrived in the Wilderness of Sin on the 15th day of the month at night,

according to the common day, that is, they packed up when the sun set on

Sabbath and traveled all night, so that they were hungry in the morning:

§524

Vs. 16:7 says the glory will appear in the morning., but the words in

the morning probably go with vs. 6. since the Hebrew is just "and morning": ![]() In that case, and morning refers to the manna, not to the display

of glory in 16:10. The text would read: "At setting you shall know

that Yahweh brought you out of the land of Egypt and morning. So

you shall see the glory of Yahweh." This does not make or break the

case here though. Like, so many attempted proofs, Coulter's

use of Exodus 16 comes up short because he assumes that the manna had to

start on Sunday morning.

In that case, and morning refers to the manna, not to the display

of glory in 16:10. The text would read: "At setting you shall know

that Yahweh brought you out of the land of Egypt and morning. So

you shall see the glory of Yahweh." This does not make or break the

case here though. Like, so many attempted proofs, Coulter's

use of Exodus 16 comes up short because he assumes that the manna had to

start on Sunday morning.

.

§525 Coulter states, 'In Exodus 30:8 it is obvious that the priest did not light the lamps in the middle of the afternoon. It is stated that the lamps were lit at "twilight, the time approaching darkness..." The Scriptures use the term ben ha arbayim, or "between the two evenings," showing that it was the time between sunset and dark.' (The Christian Passover, pg. 45).

§526 The above argument by Coulter is just plain dishonest. The words 'the time approaching darkness,' which he quotes as if it were a legitimate translation, are not represented in any Hebrew text. Moreoever, he passes this off as another proof text for ben ha arbayim, so as to mean twilight, when this text proves nothing, either way! Finally, it is only 'obvious' if we grant Coulter's mistranslation, and let him pass off 'middle of the afternoon' as if it were our position!

§527 The lamps of the mennorah were lit up shortly before sunset, not in the middle of the afternoon, which time is still 'between the settings.' In fact any moment all the way up to just before sunset is 'between the settings.' Such a procedure is quite well known to Jews, since we light the lights before sunset for the Sabbath and feast days in our homes. We do not wait till after sunset. And, in fact, such traditional lighting of the lights, reminds us of the kindling of the lights in the holy place.

§528 It is questionable scholarship that quotes a source to prove something, and then omits from that source important qualifying information that is germain to the argument. Coulter quotes BDB on page 45, "BEN HA ARBAYIM, between the two evenings ... between sunset and dark."

§529

But BDB has the words "i.e. probably" where Coulter has elipses, showning

that BDB is being tenative. After the word 'dark' BDB has '(v. Thes.

[various views fully given]', showing that the meaning has been controverted.

Another germain datum omitted by Coulter is that the Christian Church sided

with the views of minority Jewish sects on the question of the meaning

of this phrase, and that dictionaries like BDB, being of Christian production,

are likely to show some bias in that direction. Furthermore, some

recent Jewish Commentaries on the Torah have departed from the Rabbinical

interpretations of between the evenings, the most notable being The JPS

Torah Commentary: Numbers by Jacob Milgrom. But, we have already

shown that the morning and evening offerings must also be for the sabbath.

But, I might add, that if between the evenings means after sunset, then

they ought to stick with the only type of days that might allow it (the

common day, dawn to dusk day, cf. §513,

153.1), and offer the Passover offering just after sunset ending

the day part of the 14th of Aviv. But, no the neo-samaritans do not

do this. They go back to sunset at the end of the day part of the

13th of Aviv and comprehend the 14th as a standard day.

§531

Coulter's definition is actually an attempt to insert the traditional Samaritan

and Karaite view into the scriptures. The Samaritans were the colonists

imported by the Assyrians after Israel was deported. In the time

of Nehemiah they opposed God's Temple and tried to lead many Jews astray.

When Yeshua was faced with the Samaritan Woman's claim that God should

be worshipped at Mt. Gerazim according to the Samaritan teaching, he said,

"Salvation is from the Jews!" Yeshua upheld the opinions of the

Pharisees as the legitimate occupants of Moses seat, i.e. interpreters

of the law (Mt. 23:2-3a).

.

§532

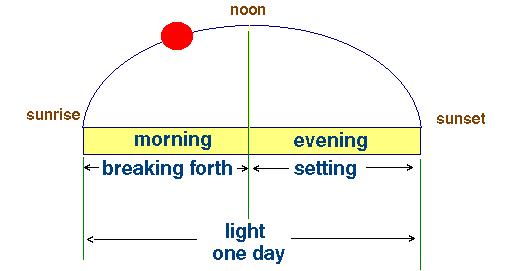

The word morning ![]() ,

means all the time from midnight to noon, just like our English word morning.

It is the exact complement of 'evening,' viz. 'setting' in Hebrew.

Morning encompasses all the time that the sun is coming up or dawning,

which begins at midnight, and ends at noon (cf.

Fig. 30). This is the period of time that the light is "breaking

forth."

,

means all the time from midnight to noon, just like our English word morning.

It is the exact complement of 'evening,' viz. 'setting' in Hebrew.

Morning encompasses all the time that the sun is coming up or dawning,

which begins at midnight, and ends at noon (cf.

Fig. 30). This is the period of time that the light is "breaking

forth."

§533

The time from midnight to dawn is called morning in English, but it is

not common to find this usage, either in English or Hebrew. It does

occur, however. Morning usually refers to dawn to noon, sunrise,

or sunrise to noon, but the meaning as applied to the period before dawn

does occur. The best example of 'morning' applying to the period

of darkness before dawn is found in Ruth 3:8, 13-14:

'And it came to pass near midnight ... Continue to abide the night ... lie down until the morning, and she had lain at his feet until the morning, but had risen before could recognize a man his friend.'It was long enough before sunrise not to recognize a friend in the dark.

§533.5 The rest of this section is superseded in the Chronology with discoveries made in the spring of 2007.

.

§537

It is important to study the Scriptures, and to compare words and texts.

The truth will come out, but most Christians never find it! They

may be saved. Yes many are! But they do not find it, because

they have fallen in too deep, the blind leading the blind, and God has

not chosen to reform all things at this time. The Holy Spirit does

not open the eyes of every believer.

Those of us who have been enlightened should count ourselves blessed and

remember that to whom is given more, more is demanded. We become

responsible to repent when our eyes are opened and walk in the path of

truth.

§537½

It is contended by those who teach the Neo-Samaritan Passover that Ezra

corupted the Torah by editing Deut. 16. This argument, of course,

is necessary, because Deut. 16 teaches that the Passover is

offered on the afternoon of the 14th. We would do well to remember

that Ezra was radically opposed by the Samaritans, who had managed to intermarry

with some of the Levites and Priests - who were forbidden to marry

any but a native Israelite. Ezra called upon the people to dissolve

these illicit marriages. The Samaritans did not want the walls of

the city rebuilt, and they did not want the Temple rebuilt. The Samaritans

only accepted the five books of Moses (in their version), and they rejected

the canon as established by Ezra and the Great Synagouge.

So, it is said, Deut. 16 contradicts the other Torah passages on the timing

of the Passover. For example Phinehas Ben Zadok argues that Deut.

16 had a redactor:

Now whether God inspired Deuteronomy as it stands, or whether Deuteronomy had a redactor (Ezra?) does not change this amazing feature, for if there was a redactor, he could never have foreseen the events of the passion-week, which needed his pen and it must be accepted, that God inspried the redactor and the redaction as it now stands (pg. 29, Which Day is the Passover?)At the very least the readactor is made into a law breaker because not but four chapters earlier it is written:

§538

Sometimes the word Passover ![]() ,

pesakh is used in the scripture to mean the passover season or other

festive offerings during the passover season, and not the passover lamb.

,

pesakh is used in the scripture to mean the passover season or other

festive offerings during the passover season, and not the passover lamb.

16.1 'Observe the Month of Aviv and keep passover season to Yahweh your Elohim. For in the Month of the Aviv Yahweh your Elohim brought you out of Mitsrayim by night. 16.2 And you shall sacrifice passover to Yahweh your Elohim from the flock or the herd at the place which Yahweh will choose to make His Name to dwell there. 16.3 You shall not eat leavened bread with it. Seven days you shall eat with it unleavened bread, the bread of affliction; for in hurried flight you came out of the land of Mitsrayim, that you may remember the day when you came out of the land of Mitsrayim all the days of your life. 16.4 And shall not be seen with you leaven in all your territory for seven days, and shall not remain any of the flesh, which you sacrifice in the setting, on the first day at the morning. 16.5 You may not sacrifice the Passover in any of your towns which Yahweh your Elohim gives to you, 16.6 but at the place which Yahweh your Elohim will choose to make his Name dwell there; you shall sacrifice the Passover in the setting, as goes down the sun, at the season you came out of Mitsrayim, 16.7 and you shall cook and eat at the place which Yahweh your Elohim will choose (near it), and you shall turn in the morning and go to your tents. 16.8 Six days you shall eat unleavened bread, then on the seventh day, you shall have a solemn assembly to Yahweh your Elohim. You shall do no work.' (Deut. 16:1-8).Pesakh may mean either the festive season, the festive sacrifices, or the official lamb.

§538.1 It is clear from Deut. 16:5-8 that the Passover lamb had to be eaten on the night of the standard 15th (the first day of unleavened bread); for only six days between (vs. 7) brings us up to the beginning of the 21st day on which there is a holy convocation. Now if the Passover lamb had been offered in the night beginning the 14th, then one would have to count seven days between to reach the 21st holy convocation. Likewise Exodus 12:15 counts "from the first day until the seventh day," which is only six days, because "until the seventh day" does not include the seventh day. Unleavened bread is eaten on the seventh day itself, but neither Exodus 12:15 or Deut. 16:8 mentions it. But Exodus 12:18-19 does.

§539 First, the festive offerings for passover season were brought for seven days, from the standard 15th to the end of the standard 21st of Aviv, and could be from the flock or or the herd, but the Passover itself had to be from the sheep or goats, not from the herd. Deuteronomy 16:2, therefore, is speaking of the festive offerings: In this regard The Soncino Press Pentateuch & Haftorahs by Dr. J.H. Hertz, Late Chief Rabbi of the British Empire, says:

[The] explanation is that the lamb was for the Paschal sacrifice, and the ox for the Festival sacrifice (). This is confirmed by what is narrated in II Chron. XXXV, 7 f. In v. 13 of that chapter, it is stated that the lambs, which were Passover-offering, 'they roasted with fire according to the ordinance'; and the oxen, which were 'the holy offerings', were boiled -- this being forbidden with the Paschal sacrifice, but allowed with the Festival-sacrifice. (Deut. 16:2).

§540

They were not allowed to boil the lamb, but had to cook

it (see quote above) by roasting. Coulter argues that 'cook' means

'boil.' It does not. It means cook in general. Exodus

recognizes this when it says, 'You shall not eat from it yet cooked

by cooking in water, but roasted' (Exodus 12:9).

The words 'in water' are necessary to clear up the ambiguity of the word

'cooked,' which does not specify exactly what kind of cooking is meant.

A woman cooked her son at the siege of Samaria; she did not boil him.

Elisha 'cooked' the oxen over a fire kindled from the yoke; he did not

boil them. The kitchens in Ezek. 46 are 'cooking' houses, not 'boiling

houses.' Therefore, Deut. 16:7 is speaking of the official Passover

offering in vs. 6.

.

§541

Many mistakenly believe that the Hebrew (see §538,

first) in Deut. 16:4 must mean 'on

the first day,' the lamb was offered, and thus either conclude that this

was not a regulation for the passover lamb, or that the 14th was also called

the "first day of unleavened bread." Both views are errors.

First, the regulation to leave none of it until morning is merely a repetition

of the original command for the Passover lamb, as they burned what remained

by midnight and left Egypt. Second, the first day of unleavened bread

is the 15th, not the 14th.

How

then can the text be explained to keep the first day of unleavened bread

on the 15th and the lamb on the 14th? The Hebrew word ![]() can mean either the first, or the former. The lexical

entry in BDB (Brown-Driver-Briggs-Gesenius, pg. 911) reads:

can mean either the first, or the former. The lexical

entry in BDB (Brown-Driver-Briggs-Gesenius, pg. 911) reads:

Holladay (A Concise Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament) elaborates:

![]()

§542

There are several reasons why the 14th of Aviv came to be called the first

day of unleavened bread also later on in Jewish history, which should not

confuse us into thinking that the biblical feast was eight days long.

The first reason is that misunderstanding Deut. 16:4 is easy, and especially

Exodus 12:15, which is mistranslated in the Greek LXX and nearly all English

translations. LXX: from yet the day, the first, you shall destroy

leaven out of the houses of you; NIV: On the first day remove the yeast

from your houses; KJV: even the first day ye shall put away leaven out

of your houses. That is not what the Hebrew says! The Hebrew

says, 'On the first day you shall have caused to be in a state of cesation

the leaven out of your houses.' In other words, all leaven

is to be gone by the time the first day arrives. That the act of

removal is not perforemed on the first day is clear from the remainder

of the verse and Exodus 12:19, 'Seven days leaven shall not be found in

your houses.' The act of removal is on the 14th, but on the 15th

leaven is taking a sabbatical cessation, and the owner causes this to be

the case by removing it before the first day begins. This is the sense

of the Hebrew imperfect in this verse.

In this

regard the commentary of the Soncino Press Pentateuch says, "Better, Of

a surety on the first day ye shall have removed the leaven from your houses"

(Exodus 12:15), and the Schocken Bible reads, "already on the first day

you are to get rid of leaven from your houses."

.

§543

Those Jews in the dispersion, reading the LXX, misunderstood the Hebrew

text, but they knew that no leaven could exist on the 15th, so they merely

assumed that the scripture also called the 14th day the first day of unleavened

bread. Likewise, they may not have recognized the possiblity of reading

Deut. 16:4 as explained above (cf. §541).

So they entered into the habit of calling both the 14th and the 15th the

first day of unleavened bread. In light of more research, however,

it appears that this usage was not in the "New Testament" (see §

.

§544

Furthermore, in the dispersion, it was not always known which day of two

possible days were declared the day of the new moon by the Beth Din in

Jerusalem. Therefore, the custom was to observe two days for each

feast day in doubt. So there came to be a first seder, and a second

seder. If the preceeding month was 30 days, then the two seders would

be the 14th and 15th of Aviv, but if it was 29 days, then they would be

the 15th and 16th of Aviv. Even in the land this doubt sometimes

resulted in the marking of both the first day of the new moon, and the

second day of the new moon (cf. I Sam. 20:18, 24, 27). What would

happen was that it became standard practice to have eight days of unleavened

bread in which the first two days were both called the first day of unleavened

bread. Josephus mentions this eight day celebration.

.

§545

Moreover, since dispersion Jewery crowded into Jerusalem at the feasts,

it was their terminology that took over. Hence, it became traditional

to call the 14th the first day of unleavened bread. And that is just

what we find in Mathew 26:17; Mark 14:12; and Luke 22:7.

.

§546

It has been established in Deuteronomy 16 that the word passover means

the passover season in general or any of the other festive offerings

brought during the passover season from the flock or the herd. Remember

that the official seder offering had to be killed between noon and sunset

on the 14th of Aviv, but the other offerings could be slain at any time

during the traditional seven days, from the 15th to the end of the

21st of Aviv. A festive sacrifice could be brought at any time to

the sanctuary, but those that were brought between sunset ending the 14th

and sunset ending the 21st were called 'passover' sacrifices, even though

they were not the official lamb.

.

§547

But, when Yayshua's disciples came to him on the 14th of Aviv, it was at

the beginning of the 14th, and they asked him where to prepare the passover.

What was meant? Since, Yayshua died on the next day, which was the

preparation of the Passover (John 19:14), it is evident that they were

asking about the Passover Seder.

.

§548

This last item is another tradition which has come into common usage: calling

a seder meal the passover. Since, no lamb was to be offered except

at the altar in Jerusalem, the dispersion Jews did not sacrifice the Passover

lamb. The meaning of the term ![]() therefore came to mean the seder meal in the dispersion, even when no lamb

was present. Therefore, by non Judean reckoning, the word pesakh

could mean one of two seder meals, taken in conjunction with the two first

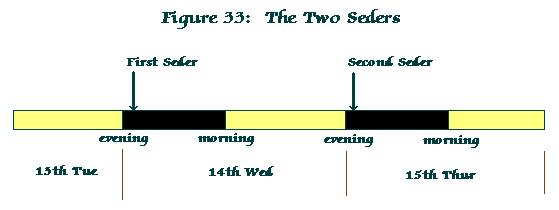

days of unleavened bread (see Fig. 33). The authors of the three

synoptic gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are non Judeans, but John a

follower of John the Baptist was probably Judean. That explains the

difference. Messianic Jewish Scholar Daivd H. Stern even goes so

far as to translate pasca as seder in The Jewish New Testament.

therefore came to mean the seder meal in the dispersion, even when no lamb

was present. Therefore, by non Judean reckoning, the word pesakh

could mean one of two seder meals, taken in conjunction with the two first

days of unleavened bread (see Fig. 33). The authors of the three

synoptic gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are non Judeans, but John a

follower of John the Baptist was probably Judean. That explains the

difference. Messianic Jewish Scholar Daivd H. Stern even goes so

far as to translate pasca as seder in The Jewish New Testament.

§549 Coulter helps us out by quoting Rabbi Shlomo Riskin:

"And it's not just the obvious fact that in the Diaspora, they celebrate an extra day at the end [of the 7-day Passover week], but surprisingly enough, an extra day at the beginning of the festival for us here in Israel" (pg. 110).Hence the double seders were on the 14 and 15th in Israel (see Fig. 33), but on the 15th and 16th elsewhere. The dispersion practice is on account of the month of Adar in the fixed calendar after 350 c.e. always being 29 days. The land practice is on account of calling the 14th the first day of unleavned bread, and the 15th the first day of unleavened bread, but before 350 c.e. Adar was not of fixed length, so even the dispersion could celebrate both the 14th and 15th. Shlomo Riskin is the dean of the Ohr Tora institutions, and chief rabbi of Efrat (The Jerusalem Post).

§550

Contrary to what Coulter teaches, the reason the lambs were slaughtered

at the Altar, according to Deut. 16, was that the Law said all sacrifices

must be brought to the place where Yahweh puts his Name. The reason

the Priests did the offerings at the time of Hezekiah and Josiah, and not

the people, was because the people were unclean and could not do it.

Hence what occured was but a logical and natural interpretation of the

Law.

Joachim Jeremias sets the record straight:

It is a fact that in Jesus' time the Passover victims were always slain in the Temple and not in private houses. This was becasue the Passover lamb was a sacrifice and its blood had to be used ceremonially.20 [note: See II Chron. 35:11 on the sprinkling of the Altar, and cf. H.L. Strack, Pesahim (Schriften des Intsitutum Judaicum in Berlin 40), Leipzig 1911, 76.] The Passover victim is expressly decribed as a sacrifice in Exodus. 12.27; 34.25; Num. 9.7 and 13; Ant. 2.312f; ... The prescriptions in Deut. 12.2,6, the precept in II Chron. 35.5f. (cf. Jub. 49.19f), and the rabbinic regulations concerning the 'lesser Holy Things' in M. Zeb. v.8 insist that the immolation take place in the Temple. This is indicated too by the fact that the bones or the kidneys of the Passover lambs were counted, a thing which would be possile only if all the slaughtering took place in the Temple. Finally, all those passages which show that the slaughtering could be done by laymen, say that is was done in the Temple: Philo ... This agress with M. Pes. v.6 which says, 'An Israelite slaughtered his (own) offering and the priest caught the blood.' In the OT the regulation in Lev. 1.5 deals with laymen slaughtering the sacrifice. It follows therefore that this ceremonial act took place in the Temple. (pg. 78-79, Jerusalem in the time of Jesus).§551 So, there was no 'domestic passover' sacrifice as Coulter insists. Coulter's view is only a Samaritan tradition so as to allow them to sacrifice it anywhere. (see §553) That is why Samaritans still offer the lamb to this day, and why the Jews will not until the Temple is rebuilt.

§552

The use of the definite article, and the occurance on the 14th show that

the sacrifice is meant, which is followed by the 15th-21st seven days of

unleavened bread. The word Chag (![]() )

means '2. festival sacrifice (cf. New [late] Hebrew

)

means '2. festival sacrifice (cf. New [late] Hebrew ![]() )

Psalm 118.27' BDB. Psalm 118:27, bind the sacrifice with cords, even

unto the horns of the altar. The Hebrew word here for sacrifice is

chag, the same word in Ezek. 45:27.

)

Psalm 118.27' BDB. Psalm 118:27, bind the sacrifice with cords, even

unto the horns of the altar. The Hebrew word here for sacrifice is

chag, the same word in Ezek. 45:27.

.

Then there shall be a place which Yahweh your Elohim shall choose to cause His name to dwell there; thither shall ye bring all that I comand you; your burnt offerings, and your sacrifices, your tithes, and the heave offering of your hand, and all the choice vows which ye vow unto Yahweh (Deut. 12:11). But at the place which Yahweh your Elohim shall choose to place His name in, there thou shalt sacrifice the passover in the setting, at the going down of the sun, at the season that thou camest forth out of Mitsrayim. (Deut. 16:6).§554 I have actually heard that some do designate a place where God puts his Name for the feast of Tabernacles, and that they argue that because they are the house of Israel that they have the right to designate a place other than the one God chooses, which is the holy place in Jerusalem. This is nothing but a renewal of the sin of Jeroboam, who built an altar, and instituted the feast of Tabernacles according to his own heart to keep the people from going up to Judah.

§555 This Passage mentions the passover observance when the children of Israel first entered the land.

'And they did the Passover§557.1 on the fourteenth day of the month in the setting,§557.2 in the plains of Jericho, and they ate out of the produce of the land on the after§557.4 the Passover,§557.3 unleavned cakes and grain on that very day.'§556 The words for the Passover here are

§558

Coulter attempts to muster Alfred Edersheim's support for his opinion that

ba erev only means sunset ending a given day (pg. 35). His

use of Edersheim is dishonest because Edersheim does not take up the meaning

of the words ba erev in the quote supplied by Coulter. And

if Edersheim had ba erev in mind, he certainly did not say that

sunset ending a stated day was its only meaning! Yet, Coulter brazenly

asserts that he has Jewish support on the matter. In fact ba erev

might mean the sunset beginning a stated day. That it does not appear

in a limited number of usages in the scripture, however, does not mean

is cannot ever mean that.

.

§559 Love is the greatest commandment. Yayshua loved his neighbor as himself, and so he did not offend his neighbors by forsaking their customs unless their customs were in contradiction to the Law. The Apostle Paul had the same attitude. To the Jew he became as a Jew, and he even followed extra traditions as long as they did not contradict the law. He also followed Gentile customs that did not contradict the law when among Gentiles.

§560 Now Coulter asserts that Yayshua was not educated as a Pharisee, and then argues that this means he never followed their legal interpretations concerning the time of Passover (pg. 187-188). This is only 1/10th true, because even though he was taught by God himself, God used human instruments, and God taught him to understand the Torah the way the Pharisees did, not the way the Sadducees did, nor the way the Samaritains did, not the way the Essenes did. So close was their agreement that Yayshua could say, "Whatever they say, that do and observe" (Mt. 23:2-3a). 'They,' of course, was the Pharisees who sat in the seat of Moshe. Now this is a commandment because the Torah commands us to listen to the judges that God puts over his people.

§561 Coulter then quotes John 7:14-15, not having learned? to prove that Yayshua had no formal education. Does the text really mean that? Not at all. That was the assumption of his audience, just as they also asssumed that he was born in Nazareth! If it proves one thing, it shows that Yayshua did not broadcast his credentials to the public.

§562 No doubt Yeshua learned to talk just like any other child, by listening to his parents! No doubt his parents had to instruct him how to do many things! After all he was human. Somebody taught him to write Hebrew, and he probably made the letters crooked like any child at first. He had human teachers, but he could still say that God taught him, because the human teachers were the instruments of God! If a human teacher instructed in error on some point, then Yayshua would be told by his Father through the Spirit what the real truth was.

§563

If Yayshua did not enroll in a Rabbinic school, he certainly participated

in discussions with them; for in Luke we are told that he was listening

to, and talking with the teachers in the temple at the age of 12, but when

he was in Samaria and the woman at the well alluded to the temple on Mt.

Gerazim, he said, "Salvation is from the Jews!" Coulter thinks that

Yayshua was 'teaching the religious leaders at the temple' (pg. 188), which

is not mentioned by Luke! Luke only mentions that he was questioning

them, and listening to them, and they were amazed at his understanding

and answers. We can assume that they asked him some questions also,

but the text does not say they were asking him to learn but it only implies

they were asking him as a teacher asked a student or a child for the correct

response.

.

§564 John's usage of the phrase passover of the Jews does not imply that it was not a feast of Yahweh. The statement of one truth does not negate another. After all, it was the Jew's passover because God passed over the Jews in Egypt! One must realize that John had a Gentile audience in Asia Minor, who were learning the Law. With all the heretical sects, viz. Samaritans, Sadducees, and Nicolaitans about, it could be argued that John had to say what kind of passover it was that Yayshua went to! After all, can a Gentile distinguish between the Samaritan Passover and the Jewish Passover without being told?

§565

As it was, it was John who was concerned about the Samaritan influence

so much that he wanted to call fire down from heaven upon them. He

was also one of the pillars along with James and Keefa at Jerusalem, and

God made them go to Samaria and lay hands on the Samaritan converts to

receive the Holy Spirit in order to make sure that they did not set up

their own leadership and cause a schism among God's people. So just

as Yayshua said, Salvation is from the Jews, John points out that

it is the Jewish Passover for the same reason.

.

§566

Remember that John's gospel was written last in about 90 c.e., and that

the Samaritan Magician Simon Magnus had probably gained quite a following

by this time, after being rejected by the Apostles. If that is the

case, then John's record of his experiences with the Samaritans is all

the more necessary.

.

§567

Coulter, of course, must twist passover of the Jews into a slur of apostacy,

because he follows the Neo-Samaritan tradition, and cannot bear to be told

that it is the Jewish Passover! What is more, but this kind of attitude

only plays into the hands of anti-semites, who say let us have nothing

in common with those Jews.

§568 John does not specify Jewish later in the book. Why is this? Because, he has already made it clear, so we may assume that the later Passover's are also Jewish passovers! Coulter misinterprets John 13:1, where it says before the feast of the Passover, when he refers it to that night, because John meant before the Passover on the next night. Why else would he call the next day the preparation of the Passover (John 19:14)? Note the absence of the words of the Jews here. Is he now going to tell us that this preparation day was the legal one because his trigger phrase does not occur? Later John does call it the preparation of the Jews in reference to the same day.

§569

The only reason John mentions Jews is because of his zeal for orthodoxy;

and part of his reason for writing his book was to correct the misuse of

the synoptic gospels account of Yeshua's seder. And no doubt, it

was those Samaritan converts, or those being influenced by them, that were

doing the absuing.

.

§569.1 It is quite probable that the Samaritan Passover was not invented by the Samaritans. After all they learned their doctrines from one of the Priests in the order of Jereboam (II Kings 17:22-41), who returned from Assyria to the high place of Bethel (II Ki. 17:28) to teach the Samaritans to fear the Lord. But the Samaritans did not love the Lord. They only feared him because of the judgments he sent upon them. For it is written:

So these nations feared Yahweh, and served their graven images, both their children, and their children's children: as did their fathers, so do they unto this day (II Kings 17:41).Now this priest was one of Jereboam's Priests, who followed the sins of Jereboam, who had ordained the feast of the seventh month to be in the eighth month (I Ki. 12:32-33), so that the people would not go up to Jerusalem. But what did he do when Passover arrived? Could it be that he changed the date and ordained a domestic one at Bethel? And then could it be that he also caused the date of Pentecost to be corrupted to be perpetually on a Sunday? If so, then he not only attacked Tabernacles, but the other two Pilgrim feasts. It does made sense for him to do a complete job, since he did not want the people to go down to Judah.

§570

In Mark 14:1 it says And It was the passover, and the unleavens,

after two days, and Luke's parallel passage supplements this by

spelling out the feast of unleavens, so it is clear that

the gospels are saying that the passover and the feast of unleavened bread

both occur after two days, which means they both occur on the same day.

So there are not two separate feasts, but only one.

Furthermore,

the day that is after two days is viewed as a common day (sunrise Wed.

to sunrise Thur), so that the statement was made on Monday-Tuesday (sunrise

Mon to sunrise Tue). Yayshua was at Bethany on Monday night (Mk.

14:3). In the morning it was "after one day," and he ate the first

Seder with his disciples on Tuesday night. In the morning (sunrise)

it was "after two days," so that the Passover sacrifice, Yayshua's death,

and the Second Seder all fall "after two days".

§571

It is also clear that the word passover here must mean the slaying of the

lamb and not the eating of it at the 15th seder, because Yayshua adds and

the Son of man will be delivered up to be put to death (Mt. 26:2),

which means that we are talking about the common 14th, not the standard

15th, because by sunset of the 15th, Yayshua was in the grave. For

it is clear that he died on the 'preparation of the passover,' which is

the 14th.

§572

[revised]

.

§573

And toward the first day of the feast of unleavened bread, when the

passover they sacrificed ... (Mk. 14:12). Luke supplements

with: on which it was necessary to sacrifice the passover.

So the gospel writers are refering to the 14th, but is is also clear that

it is the beginning of the 14th because Yeshua was eating the first seder,

and it was the preparation of the passover (John 19:14).

§574

The standard 14th lasts from sunset to sunset. Now the KJV

has correctly translated the text when they killed the passover, and Bullinger

has a note on killed = were wont to kill, which means when they were accustomed

to kill it, viz. on that day. But the text does not say when on that

day! It just says, when they were accustomed to sacrifice the passover.

It is also clear that it is speaking about the official lamb, because Luke

says it was necessary. Only the other festive offerings were optional

for the people.

§575

Now Coulter argues that the Greek word here ![]() means

'they were killing' the passover. He only displays his ignorance

of the Greek imperfect tense, when he argues that it must mean they were

doing the killing at that moment (pg. 197). For this imperfect, as

pointed out by the Linguistic Key to the Greek New Testament (Fritz

Rienecker/Cleon Rogers: Zondervan) is a "customary" imperfect (pg. 127;

Mk 14:12). The action is durative or linear not in a continuous sense

but in a repetitive sense, viz. when the passover they repeatedly

killed, and the repetition refers to the year by year killing on the 14th.

That is why this imperfect is called 'customary.' (See A.T. Robertson,

pg. 884, 'The Iterative (Customary) Imperfect.')

means

'they were killing' the passover. He only displays his ignorance

of the Greek imperfect tense, when he argues that it must mean they were

doing the killing at that moment (pg. 197). For this imperfect, as

pointed out by the Linguistic Key to the Greek New Testament (Fritz

Rienecker/Cleon Rogers: Zondervan) is a "customary" imperfect (pg. 127;

Mk 14:12). The action is durative or linear not in a continuous sense

but in a repetitive sense, viz. when the passover they repeatedly

killed, and the repetition refers to the year by year killing on the 14th.

That is why this imperfect is called 'customary.' (See A.T. Robertson,

pg. 884, 'The Iterative (Customary) Imperfect.')

So Mark is simply stating that it was customary to kill the passover lamb

on that day, which lasts from sunset to sunset. Now it must

be noted that I have translated the words "And toward the first

day"'; the Greek is actually a dative, and this is the "to" or "for"

case in Greek. Matthew says, "The first day of unleavens approached",

which is to say, it was not yet the first day of unleavened bread (Mt.

26:17), and Luke might seem difficult, but we have a textual variant that

reads, "And came the day of the Passover on which it was necessary

to slay the passover lamb" (Luke 22:7). The "day of unleavens" is

strictly the 15th, but "passover" can mean the 14th, so the textual variant

saves the day. Hence in all three cases, it is not stated that it

is the first day of unleavened bread, but only that it is either the passover

or approaching the first day.

.

§576

Now I have said before that in the case in which Adar or Adar II had 30

days, the proper days of Aviv for celebrating passover in the case that

the new moon was ambiguous were the 14th and 15th of Aviv. For if

Adar was actually 29 days, then the 14th of Aviv would turn out to be the

legal 15th. Now in the years 28-35, Adar had 30 days in every year

except 33 c.e., and 33 c.e. rules itself out since Yayshua did not die

on Friday (Mt. 12:40).

§577

Also, as I have said, it was a dispersion practice to always have two seders,

which they called the Passover, on the double first days of unleavened

bread. Preparing such a seder would be called preparing the Passover

in disaspora parlance. (Now, I also allude to the fact that the dispersion

habit of having it always on the 15th and 16th grew up after the introduction

of the fixed calendar in 350 c.e., in which the final Adar always had 29

days.) But, in the year Messiah died, Adar was 30 days, so it follows

that the first seder was on the 14th.

§578

Now, notice that Matthew, Mark, and Luke speak of Peter and John 'preparing

the passover,' not sacrificing it. This is because in practice they

could have the two seders, but they could not sacrifice two lambs, one

on each night. They may have had a festive lamb on the first night,

but that would not be regarded as the official lamb.

§579

Now, should Coulter make much ado about the fact that the definite article

is used, viz 'they prepared the passover,' I must point out that I have

already said that in Greek the matter has been reduced to ambiguity by

the LXX, and in modern Hebrew also.

.

§580

Coulter says that there was not enough time to slay all the passover lambs

or goats in the Temple (pg. 198). Is this true? Based on Jeremias

calculations Coulter allows for 19,200 victims (pg. 181) at maximum capacity.

Then after citing Josephus figure of 2,700,000 people at Jerusalem in 70

c.e., he concludes that there was in no way enough lambs for them all.

§581

Josephus, Jeremias, and Coulter all ignore the flexiblity of the situation.

First, the number of participants that ate each lamb can be increased from

10 to 15, and even to 20 if necessary, viz:

§582 Discovering the City of Ramesses:

In 1966, an Austrian archaeological team, headed by Dr. Manfred Bietak, began long-term excavations four miles north of the delta town of Faqus -- at a site called Tell el-Dab'a. Bietak was aware that this site had an earlier name, tell el-Birka -"the mound of the LAKE." Old maps revealed that this lake was at one time joined to the old Pelusiac branch of the Nile by an artificial waterway that anciently encircled the whole area. When aerial photography revealed the ancient bed of the Pelusaic branch of the Nile, Bietak was convinced he had found the SITE OF RAMESSES.But what is also quite obvious from Dr. Bietak's findings is that not only was this site the TRUE BIBLICAL RAMESSES, it quite evidently had a history MUCH EARLIER than the time of Ramesses II. as well, and was in fact none other than the HYKSOS CAPITAL, AVARIS, referred to in Manetho's History. -- The Exodus Enigma, by Ian Wilson. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London. 1985. Pp. 48, 49 & 52.During the 1979-80 excavation season, Bietak realized that the city had been built DURING THE 12TH DYNASTY BY AMENEMHET I. -WITH ADDITIONS AND/OR REBUILDING BY SENWOSRET III. OF THE SAME DYNASTY!

Some FIVE HUNDRED YEARS BEFORE THE TIME OF RAMESSES II. this had been a CAREFULLY LAID OUT CITY of some importance during the time of Egypt's MIDDLE KINGDOM, a century or so PRIOR to Egypt's takeover by the Hyksos. Readily discernible were the foundations of an imposing 450-foot-long palace, with a huge court lined by columns, that had probably served as a ROYAL SUMMER RESIDENCE....Records show that order [in Egypt] was reestablished by STRONG GOVERNMENT on the part of the kings of Egypt's MIDDLE KINGDOM, and IT IS TO THESE THAT CAN BE ATTRIBUTED THE COLUMNED PALACE west of the Tell el-Dab'a mound, as well as a variety of OTHER BUILDINGS AND MONUMENTS that seem to have surrounded the Birka lake. One of these, a TEMPLE OF THE EGYPTIAN KING AMENEMHET I., was found to contain a tablet specifically referring to the 'TEMPLE OF AMENEMHET in [at] the water of the town' -- independent corroboration of the town's abundance of water....

§583

What this reveals is that Ra'amses was on the far eastern side of the Nile

Delta. Going east of Ra'amses meant going out of Egypt. Furthermore,

the entire land of Goshen was next to Ra'amses, and was within 10 miles

of the city (Goshen was 20 miles by 15 miles, pg. 56), a distance that

can be covered in 3 hours in haste. Ra'amses was the city that the

sons of Israel were compelled to build. Now, the sons of Israel were

shepherds, and roamed the land of Goshen to find pasturage for their sheep,

but when they were made slaves, they had to serve at the site of Ra'amses,

which means they had to be provided with, or more likely had to build their

own houses in and around Ra'ames. Furthermore, it was the end of

winter, when the woman and children stayed with the menfolk who were forced

to serve. In the Spring, Summer, and Fall the woman and children

took care of the flocks in the land of Goshen. Now even if

they had been scattered around the countryside taking care of flocks early

in the Spring, they had all gathered to their homes anyway in preparation

for the Exodus - along with their flocks. The poor had only homes

in Ra'amses, but the better positioned slaves may have had a residence

in another part of Goshen, but they still had to maintain a primary dwelling

where they were serving, viz. Ra'amses.

§584

The servitude imposed upon the sons of Israel after building the store

cities was the manufacture of bricks. The bricks were probably made

in Pitom and Ra'amses and shipped elsewhere in Egypt up the Nile, but the

Israelites had not been serving since the plague of darkness, and had all

gathered to the dwellings they were forced to maintain in the city.

At any rate, if they ate it in some other part of Goshen, the average trip

to Ra'amses would be 5 miles and could be walked in 2 hours.

§585

Coulter, however, in analyzing Josephus' explanation states that Josephus,

'tells us that the children of Israel left their houses and were gathered

at one place before the Passover.' (pg. 53). Then he quotes Josephus

saying, 'and purified their houses' (pg. 53), and implies that Josephus

is contradicting himself! However, his alleged quote (underlined)

from Josephus is fiction! Completely mythical! For all he said was

that Moses 'kept them together in one place;' Josephus did not say

thay left their houses, nor that they had left the principal city in Goshen,

where most of the houses would logically be. No doubt there were

villages around the land, but they could have reached Ra'amses in haste

between 12 a.m. and 5 a.m. And since, they had been warned to be

ready, many joined houses that were not on the outskirts of the land.

§586

To be sure, even if they had no homes in Ra'amses, Coulter merely assumes

that they could not reach the city that night, and then leave Egypt!

Goshen is only 15 x 20 miles, and Ra'amses is on the border of Goshen,

and Goshen itself is on the border of Egypt. Now the 20 miles runs

the length of the Pelusian Nile (the eastern most branch), so it is only

15 miles from any part of Goshen out of Egypt. And if one must go

through Ra'amses (optimally placed), the maximum distance is sqr(102+152)=18

miles, which can be covered in 6 hours @ 3mph for walking, and in less

if at a trot, riding part way on the livestock or jogging, which would

fit with the haste in which they left.

§587

We really do not know the precise circumstances though. It is merely

enough to suggest some alternatives that invalidate Coulter's theory, which

falls apart like the theories of those who claim that there was not enough

room on the ark for all the animals.

.

And not you shall cause to remain out of it until morning, and that which remains out of it until morning in the fire you shall burn. (Exodus 12:10).Therefore, it had to be burned in the house fire, so only a house with a fireplace inside would suffice. The command clearly implies that none of the consumable part is to remain until the morning, and then adds that the unconsumable part must be burned in the fire. Now burned in fire does not mean that the fire must burn the bones into ash, but only to burn off all remaining fat and meat. For Exodus 12:46 says

In one house it shall be eaten; not shall go out from the house any of the flesh outside, and a bone you shall not break.If any attempt is made to burn up the bones to ash they will surely break in the narrow spots. That is why the Jews count and bury the bones of the Passover sacrifice.

§589

Coulter assumes that the bones had to be burned to ash and so he adds hours

of delay to their departure, and he concludes that it would take 8-10 hours

to kill, roast, eat, and burn a Passover lamb, and that they could not

be done before 2 in the morning (pg. 60). Of course he assumes that

they slew and roasted it after sunset, but that is not fair, because he

is attempting to show the impossibility of the orthodox view, which requires

the lambs to be slain in the afternoon, between the settings.

If the last lamb was slain at 2 p.m., then they could cook it from 2 to

7 p.m., and then eat it from 7 p.m. to 8 p.m. in haste and still have 4

hours left to burn it, and Coulter allows 2-3 hours to burn it, and if

they needed it, they had 12 hours to complete the whole process, from noon

to midnight, which is 4 hours in excess of the time Coulter says is required.

.

§598.01 Harry Veerman (Phinehas Ben Zadok) writes:

It is inconceivable, that the Egyptians would have conceded to the Israelites' demands for jewelry and raiment before Pharoah was forced to thrust them out of the land (Which Day is the Passover, pg. 12)But is it? Consider the following facts: the Egyptians has just endured the ravages of 9 plauges, and even Pharoah's officials begged him to let the people go. It was Pharoah's heart that was hardened, not the rest of Egypt. Their crops were ruined, and their gods were proven to be impotent, and the promise of another plauge was on the way. Furthermore, Pharoah had said they could go, and then relented at the last minute several times. He may have been personally relieved to see the plauges stopped, but Egypt was not. Egypt was lost and he did not know it. It is likely that the people of Egypt were giving them whatever they asked for before, during and after the last plauge (see below §589.03). Yes, even on the way to Ra'amses, Israel could have plundered Egypt on the way out.

§589.02 Mr. Veerman also writes:

We may ask: "Why the haste?" It was the Egyptians, who were in haste to send the Israelites away after the tenth plauge had done its terrible work. As far as the children of Israel were concerned: they had to kill the lamb in the evening (at dusk; between the two evening times; Hebr.: ben ha'arbayim). It takes at least three hours to thoroughly roast a whole lamb. Therefore there were about nine hours of darkness left in which to consume the lamb with the matzot (unleavened bread) and bitter herbs. Then at daybreak, if any flesh was till uneaten, it had to be burned, so that nothing remained of it. There does not seem to be any need for haste at all, since the people were forbidden to leave their houses until the morning (pg. 13)..I explained to Mr. Veerman, in person, that "morning" in Egypt meant midnight (see §532-533), a notion which he dismissed. The lamb was slain between noon and sunset on the 14th, and eaten, and burned between sunset and midnight on the 15th. Either view provides exactly the same amount of time (12 hours: see §588-589), except in his view they left Egypt after waiting the whole next day so that it could be night when they left (Deut. 16:1-2). So in his view there was no need for the haste of not letting the bread rise, or forgetting to prepare provisions for the journey (see §535-536), hence his comments above.

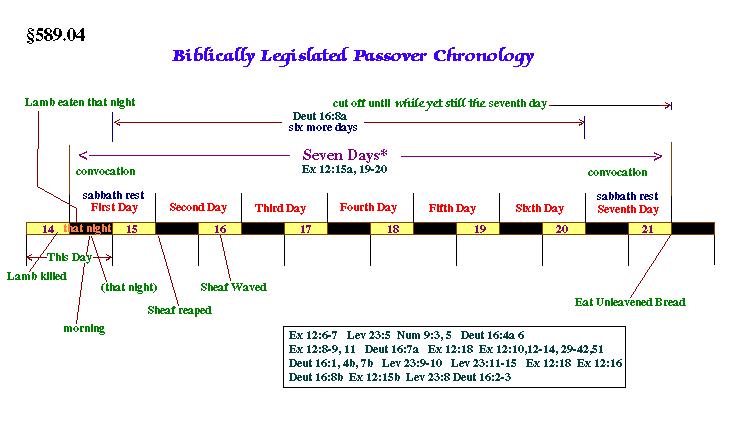

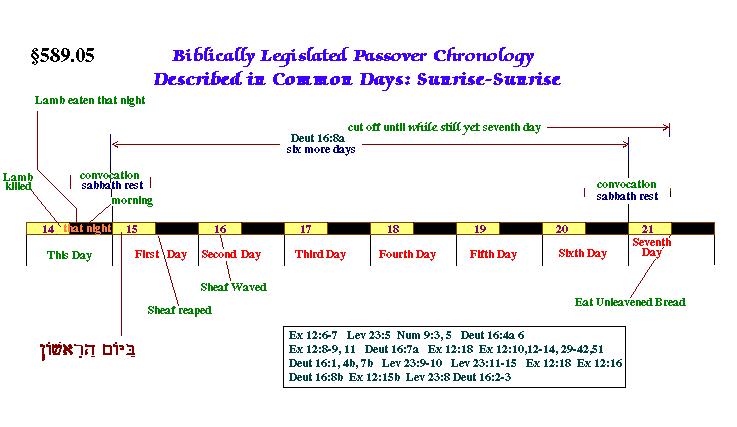

§589.035

The diagram in §589.04-§589.05

shows how the Passover laws relate to the standard

and common days. It ought to be noted that

when Yayshua said he would rise "the third day," that it would be the 16th

of Aviv by the common day. It should also be noted that both Exodus

12:15b and Deut. 16:8a legislate unleavened bread up to the end of the

sixth day, but that Exodus 12:15a, 18-20, and Lev. 23:8 legislate it to

the end of the seventh day. Thus the first two verses only give part

of the period, while the latter verses give the whole of it. The

reason for this reckoning is that some of the passages use the common

day, which explanation shows that the Neo-Samaritan theory

is untenable (cf. §538.1).

legacy name: www.parsimony.org